His prayer is all the world’s – and mine.

One attractive aspect I find in Kipling is his respect for all religious beliefs. While a non-theist himself, his attitude was a comprehensive tolerance of all faiths and utter condemnation of any form of religious intolerance and bigotry. In ‘Kim’, Kipling’s best-known novel, he describes the meeting between Bennett (the Church of England military chaplain) and the Buddhist lama (Kim’s spiritual master) with the scathing remark: ‘Bennett looked at him with the triple-ringed uninterest of the creed that lumps nine-tenths of the world under the title of ‘heathen’.’

Both of Kipling’s grandfathers as well as his uncle were Methodist ministers, but he did not believe in Christian dogma. Perhaps this is why Buddhism had a special appeal for him, as Buddhism avoids speculation about the nature of God and concentrates instead on dharma – the moral law for people to live by. The poem ‘Buddha at Kamakura’ is full of reverence for Buddhism and rebukes Western missionaries who attack it and tourists who ridicule it. And in the poem ‘Jobson’s Amen’, Kipling makes his strongest statement of refusing to judge other creeds.

Kipling wrote, ‘Every man has to work out his creed according to his own wave-length, and the hope is that the Great Receiving Station is tuned to take all wave-lengths’. His belief in the essential value of all religions and the unity of mankind is summed up in the short poem ‘The Prayer’ (which, appropriately, heads one of the chapters of ‘Kim’ ): His God is as his fates assign, / his prayer is all the world’s – and mine.

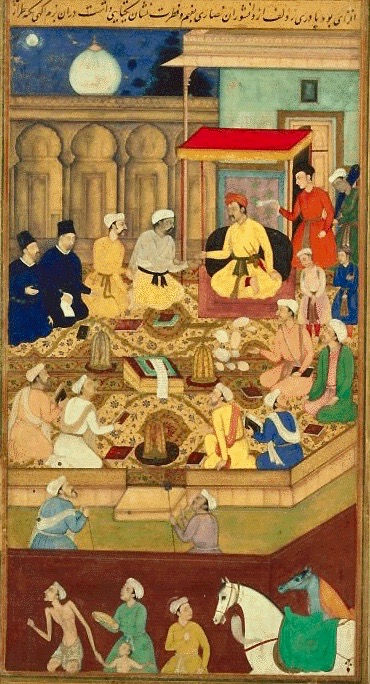

The picture shows the Emperor Akbar (who had respect for all religions) receiving Jesuit missionaries.