Lord, send a man like Robbie Burns to sing the Song o’ Steam!

This is a sister poem to “The Mary Gloster”, in which Sir Anthony Gloster mentions his former employee McAndrew as the only man he can trust:

“Stiff-necked Glasgow beggar! I’ve heard he’s prayed for my soul / But he couldn’t lie if you paid him, and he’d starve before he stole …”

The difference between the two men could not be greater: Sir Anthony Gloster is a shipping tycoon who dines with royalty, but is a tormented man driven by an obsession; while his employee McAndrew, “the dour Scots engineer, the man they never knew”, has achieved neither fame nor riches, but has made peace with his soul and the world. T.S. Eliot aptly called Sir Anthony Gloster “the failure of success” and McAndrew “the success of failure”. It is significant that at his hour of death, Sir Anthony Gloster has only his decadent son to talk to; but the solitary McAndrew talks with God.

McAndrew’s Scottish Calvinism taught that people must lead a life of work and prayer, devoid of physical pleasures, but that because of Original Sin even all this effort cannot guarantee salvation – only God’s Grace can do that. These Calvinist deadly virtues certainly run through the poem. Yet, ‘McAndrew’s Hymn’ may be unparalleled as a poetic portrayal of the positive aspects of the Protestant Ethic: work as a form of worship, finding self-realization in doing one’s duty, taking responsibility without expecting credit:

“But I ha’ lived an’ I ha’ worked. Be thanks to Thee, Most High! / “An’ I ha’ done what I ha’ done – judge Thou if ill or well – …”

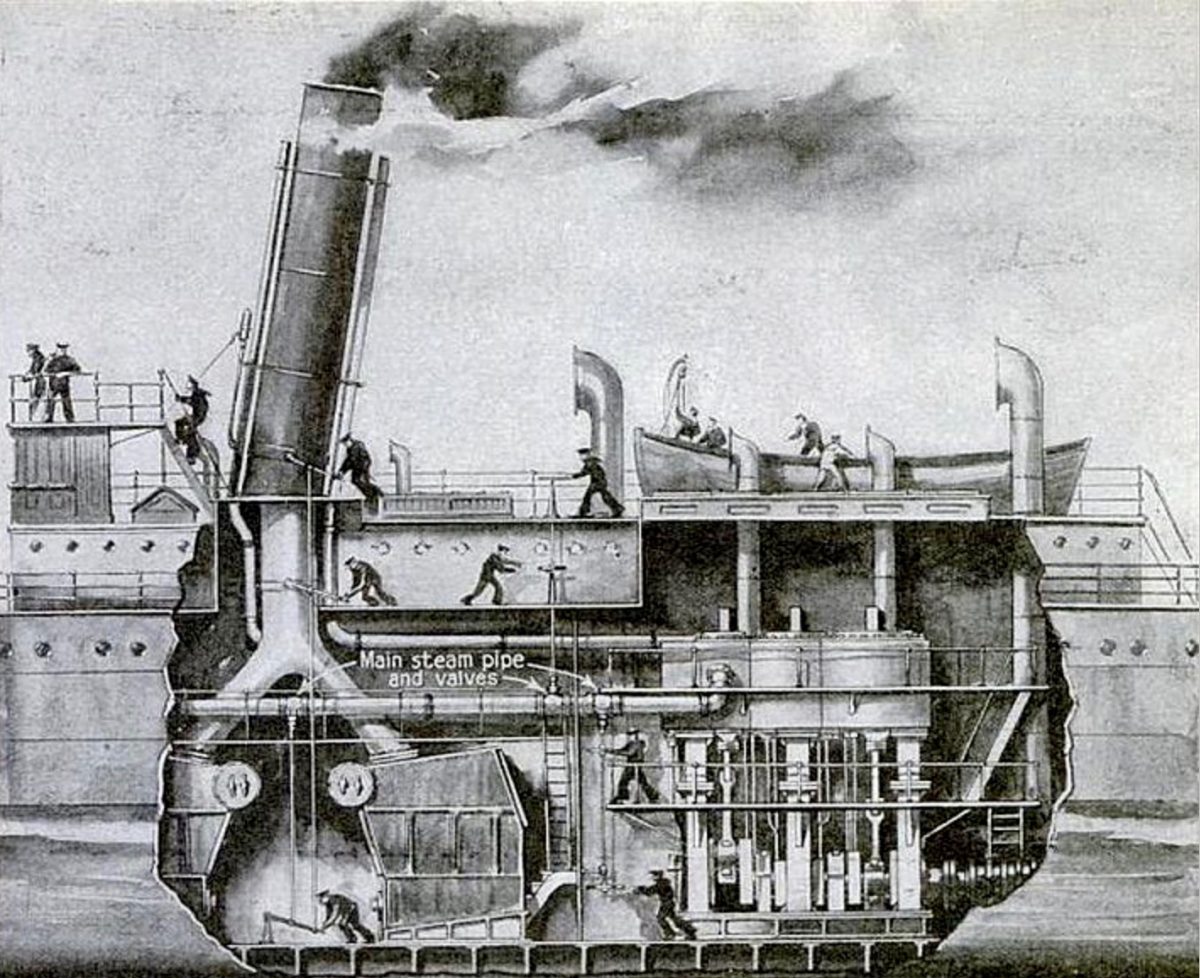

Kipling had a life-long fascination with machinery. He was an early motor-car enthusiast and a frequent visitor aboard British Navy vessels. Whereas the Aesthetes, who were the main literary current in his time, revolted against the ugliness of industrialization, Kipling found machines exhilarating. His McAndrew exalts: “… my seven thousand horse-power here. Eh, Lord! They’re grand – they’re grand!” Kipling wrote many short stories about machinery. Moreover, as far as I know, Kipling was the first to make machinery the subject of poetry. Towards the end of “McAndrew’s Hymn”, McAndrew wishes for “a man like Robbie Burns to sing the Song of Steam”. Kipling was too unassuming to claim that he himself was that man; but no other has appeared, and no one could have done it better. The last page of the poem describes so superbly the crescendo of noises in the ship’s engine-room that it sounds like the Music of the Spheres.

A good dramatic monologue can reveal about the speaker things of which the speaker himself is unaware. In the case of McAndrew we see that behind the public face of the proverbially stingy Scotsman who orders the oiler to wipe off excess oil and use it again, there is a private man who loves small children, who allows his beloved machines to “knock a wee”, who spoils them with the best coal, and who sublimates his repressed sexuality – which runs as an undercurrent throughout the poem – by identifying with his colleague Ferguson who is impatient to reunite with his wife.

One of Kipling’s less admirable habits is to inflict upon the reader his accurate and detailed knowledge of little-known technical terms for parts of steamship engines, or of names of exotic places and of Scottish dialect words. But do not let the unfamiliar terms deter you – skip over them and read on, and you’ll be rewarded by accompanying McAndrew on a journey around the world, through his life and into his soul.

McAndrew’s Hymn

Lord, Thou hast made this world below the shadow of a dream, An', taught by time, I tak' it so - exceptin' always Steam. From coupler-flange to spindle-guide I see Thy Hand, O God - Predestination in the stride o' yon connectin'-rod. John Calvin might ha' forged the same - enorrmous, certain, slow - Ay, wrought it in the furnace-flame - my "Institutio". (1) I cannot get my sleep to-night; old bones are hard to please; I'll stand the middle watch up here - alone wi' God an' these My engines, after ninety days o' race an' rack an' strain Through all the seas of all Thy world, slam-bangin' home again. Slam-bang too much - they knock a wee - the crosshead-gibs are loose, But thirty thousand mile o' sea has gied them fair excuse.... Fine, clear an' dark - a full-draught breeze, wi' Ushant out o' sight,( 2) An' Ferguson relievin' Hay. Old girl, ye'll walk to-night! His wife's at Plymouth... Seventy - One - Two - Three since he began - Three turns for Mistress Ferguson ... and who's to blame the man? There's none at any port for me, by drivin' fast or slow, Since Elsie Campbell went to Thee, Lord, thirty years ago. (The year the Sarah Sands was burned. Oh, roads we used to tread, Fra' Maryhill to Pollokshaws - fra' Govan to Parkhead!) Not but they're ceevil on the Board. Ye'll hear Sir Kenneth say: "Good morrn, McAndrew! Back again? An' how's your bilge to-day?" Miscallin' technicalities but handin' me my chair To drink Madeira wi' three Earls - the auld Fleet Engineer That started as a boiler-whelp - when steam and he were low. I mind the time we used to serve a broken pipe wi' tow! (3) Ten pound was all the pressure then - Eh! Eh! - a man wad drive; An' here, our workin' gauges give one hunder sixty-five! We're creepin' on wi' each new rig - less weight an' larger power; There'll be the loco-boiler next an' thirty mile an hour! Thirty an' more. What I ha' seen since ocean-steam began Leaves me na doot for the machine: but what about the man? The man that counts, wi' all his runs, one million mile o' sea: Four time the span from earth to moon.... How far, O Lord, from Thee That wast beside him night an' day? Ye mind my first typhoon? It scoughed the skipper on his way to jock wi' the saloon. Three feet were on the stokehold-floor - just slappin' to an' fro - An' cast me on a furnace-door. I have the marks to show. Marks! I ha' marks o' more than burns - deep in my soul an' black, An' times like this, when things go smooth, my wickudness comes back. The sins o' four an' forty years, all up an' down the seas. Clack an' repeat like valves half-fed.... Forgie's our trespasses! Nights when I'd come on deck to mark, wi' envy in my gaze, The couples kittlin' in the dark between the funnel-stays; Years when I raked the Ports wi' pride to fill my cup o' wrong - Judge not, O Lord, my steps aside at Gay Street in Hong-Kong! Blot out the wastrel hours of mine in sin when I abode - Jane Harrigan's an' Number Nine, The Reddick an' Grant Road! An' waur than all - my crownin' sin - rank blasphemy an' wild. I was not four and twenty then - Ye wadna judge a child? I'd seen the Tropics first that run - new fruit, new smells, new air - How could I tell - blind-fou wi' sun - the Deil was lurkin' there? By day like playhouse-scenes the shore slid past our sleepy eyes; By night those soft, lasceevious stars leered from those velvet skies, In port (we used no cargo-steam) I'd daunder down the streets - An ijjit grinnin' in a dream - for shells an' parrakeets, An' walkin'-sticks o' carved bamboo an' blowfish stuffed an' dried - Fillin' my bunk wi' rubbishry the Chief put overside. Till, off Sambawa Head, Ye mind, I heard a land-breeze ca', Milk-warm wi' breath o' spice an' bloom: "McAndrew, come awa'!" Firm, clear an' low - no haste, no hate - the ghostly whisper went, Just statin' eevidential facts beyon' all argument: "Your mither's God's a graspin' deil, the shadow o' yoursel', "Got out o' books by meenisters clean daft on Heaven an' Hell. "They mak' him in the Broomielaw, o' Glasgie cold an' dirt, "A jealous, pridefu' fetich, lad, that's only strong to hurt. "Ye'll not go back to Him again an' kiss His red-hot rod, "But come wi' Us" (Now, who were they?) "an' know the Leevin' God, "That does not kipper souls for sport or break a life in jest, "But swells the ripenin' cocoanuts an' ripes the woman's breast." An' there it stopped - cut off - no more - that quiet, certain voice - For me, six months o' twenty-four, to leave or take at choice. 'Twas on me like a thunderclap - it racked me through an' through - Temptation past the show o' speech, unnameable an' new - The Sin against the Holy Ghost? ... An' under all, our screw. (4) That storm blew by but left behind her anchor-shiftin' swell. Thou knowest all my heart an' mind, Thou knowest, Lord, I fell - Third on the Mary Gloster then, and first that night in Hell! Yet was Thy Hand beneath my head, about my feet Thy Care - Fra' Deli clear to Torres Strait, the trial o' despair, But when we touched the Barrier Reef Thy answer to my prayer!... We dared na run that sea by night but lay an' held our fire, An' I was drowsin' in the hatch - sick - sick wi' doubt an' tire: "Better the sight of eyes that see than wanderin' o' desire!" Ye mind that word? Clear as our gongs - again, an' once again, When rippin' down through coral-trash ran out our moorin'-chain: An', by Thy Grace, I had the Light to see my duty plain. Light on the engine-room - no more - bright as our carbons burn. I've lost it since a thousand times, but never past return! (5) . . . . . . . . . . Obsairve! Per annum we'll have here two thousand souls aboard - Think not I dare to justify myself before the Lord, But - average fifteen hunder souls safe-borne fra' port to port - I am o' service to my kind. Ye wadna blame the thought? Maybe they steam from Grace to Wrath - to sin by folly led - It isna mine to judge their path - their lives are on my head. Mine at the last - when all is done it all comes back to me, The fault that leaves six thousand ton a log upon the sea. We'll tak' one stretch - three weeks an' odd by ony road ye steer - Fra' Cape Town east to Wellington - ye need an engineer. Fail there - ye've time to weld your shaft - ay, eat it, ere ye're spoke; Or make Kerguelen under sail - three jiggers burned wi' smoke! (6) An' home again - the Rio run : It's no child's play to go (7) Steamin' to bell for fourteen days o' snow an' floe an' blow. The bergs like kelpies overside that girn an' turn an' shift (8) Whaur, grindin' like the Mills o' God, goes by the big South drift. (Hail, Snow and Ice that praise the Lord. I've met them at their work, An' wished we had anither route or they anither kirk.) Yon's strain, hard strain, o' head an' hand, for though Thy Power brings All skill to naught, Ye'll understand a man must think o' things. Then, at the last, we'll get to port an' hoist their baggage clear - The passengers, wi' gloves an' canes - an' this is what I'll hear: "Well, thank ye for a pleasant voyage. The tender's comin' now." (9) While I go testin' follower-bolts an' watch the skipper bow. They've words for every one but me - shake hands wi' half the crew, Except the dour Scots engineer, the man they never knew. An' yet I like the wark for all we've dam'-few pickin's here - No pension, an' the most we'll earn's four hunder pound a year. Better myself abroad? Maybe. I'd sooner starve than sail Wi' such as call a snifter-rod ross.... French for nightingale. (10) Commeesion on my stores? Some do; but I cannot afford To lie like stewards wi' patty-pans. I'm older than the Board. A bonus on the coal I save? Ou ay, the Scots are close, (11) But when I grudge the strength Ye gave I'll grudge their food to those. (There's bricks that I might recommend - an' clink the fire-bars cruel. No! Welsh - Wangarti at the worst - an' damn all patent fuel!) (12) Inventions? Ye must stay in port to mak' a patent pay. My Deeferential Valve-Gear taught me how that business lay. I blame no chaps wi' clearer heads for aught they make or sell. I found that I could not invent an' look to these as well. So, wrestled wi' Apollyon - Nah! - fretted like a bairn - (13) But burned the workin'-plans last run, wi' all I hoped to earn. Ye know how hard an Idol dies, an' what that meant to me - E'en ta' it for a sacrifice acceptable to Thee.... Below there! Oiler! What's your wark? Ye find it runnin' hard? Ye needn't swill the cup wi' oil - this isn't the Cunard! Ye thought? Ye are not paid to think. Go, sweat that off again! Tck! Tck! It's deeficult to sweer nor tak' The Name in vain! Men, ay, an' women, call me stern. Wi' these to oversee, Ye'll note I've little time to burn on social repartee. The bairns see what their elders miss; they'll hunt me to an' fro, Till for the sake of - well, a kiss - I tak' 'em down below. That minds me of our Viscount loon - Sir Kenneth's kin - the chap Wi' Russia leather tennis-shoon an' spar-decked yachtin'-cap. I showed him round last week, o'er all - an' at the last says he: "Mister McAndrew, don't you think steam spoils romance at sea?" Damned ijjit! I'd been doon that morn to see what ailed the throws, Manholin', on my back - tha cranks three inches off my nose. Romance! Those first-class passengers they like it very well, Printed an' bound in little books; but why don't poets tell? I'm sick of all their quirks an' turns - the loves an' doves they dream - Lord, send a man like Robbie Burns to sing the Song o' Steam! To match wi' Scotia's noblest speech yon orchestra sublime Whaurto - uplifted like the Just - the tail-rods mark the time. The crank-throws give the double-bass, the feed-pump sobs an' heaves, An' now the main eccentrics start their quarrel on the sheaves: Her time, her own appointed time, the rocking link-head bides, Till - hear that note? - the rod's return whings glimmerin' through the guides. They're all awa'! True beat, full power, the clangin' chorus goes Clear to the tunnel where they sit, my purrin' dynamoes. Interdependence absolute, foreseen, ordained, decreed, To work, Ye'll note, at ony tilt an' every rate o' speed. Fra skylight-lift to furnace-bars, backed, bolted, braced an' stayed, An' singin' like the Mornin' Stars for joy that they are made; While, out o' touch o' vanity, the sweatin' thrust-block says: "Not unto us the praise, or man - not unto us the praise!" Now, a' together, hear them lift their lesson - theirs an' mine: "Law, Orrder, Duty an' Restraint, Obedience, Discipline!" Mill, forge an' try-pit taught them that when roarin' they arose, An' whiles I wonder if a soul was gied them wi' the blows. Oh for a man to weld it then, in one trip-hammer strain, Till even first-class passengers could tell the meanin' plain! But no one cares except mysel' that serve an' understand My seven thousand horse-power here. Eh, Lord! They're grand - they're grand! Uplift am I? When first in store the new-made beasties stood, Were Ye cast down that breathed the Word declarin' all things good? Not so! O' that warld-liftin' joy no after-fall could vex, Ye've left a glimmer still to cheer the Man - the Arrtifex! (14) That holds, in spite o' knock and scale, o' friction, waste an' slip, An' by that light - now, mark my word - we'll build the Perfect Ship. (15) I'll never last to judge her lines or take her curve - not I. But I ha' lived an' I ha' worked. Be thanks to Thee, Most High! An' I ha' done what I ha' done - judge Thou if ill or well - Always Thy grace preventing' me .... Losh! Yon's the "Stand-by" bell. Pilot so soon? His flare it is. The mornin'-watch is set. Well, God be thanked, as I was sayin', I'm no Pelagian yet. (16) Now I'll tak' on.... 'Morrn, Ferguson. Man, have ye ever thought What your good leddy costs in coal? ... I'll burn 'em down to port. (17)

Notes

[1] “Institution de la Religion Chrétienne” is the major work of John Calvin, the founder of Calvinism. It had an enormous influence in England and particularly in Scotland. The “Institution” advocates the doctrines of Original Sin and God’s Grace, which reverberate through the poem.

[2] Ushant is at the westernmost tip of France – Finisterre (Land’s End); thus they are nearing England again after a round-the-world cruise – “thirty thousand mile o’ sea” – a good time to reflect on the voyage and take stock of one’s life.

[3] ‘Serve a broken pipe wi’ tow’ – when the pressure was so low that a broken pipe could be sealed by binding it with rope.

[4] Seafarers have often noted that the constant throbbing of the ship’s screw loosens people’s inhibitions – here intensifying the young McAndrew’s sexual tensions.

[5] The mystics say that “when the student is ready, the teacher appears” – when one’s mind is truly open and tuned in, anybody or anything can be the teacher – even an ant. In the case of McAndrew, a simple light in the engine-room made him literally “see the Light”.

[6] One of the world’s most desolate sea-routes is from Cape Town across the southern Indian Ocean to Wellington, New Zealand – over three weeks with a ship of McAndrew’s days. If the main shaft breaks on this route, you’d have time to weld it – or even to eat it – “ere ye’re spoke”, i.e. before another ship sights and hails you. The only alternative would be to hang jiggers (small aft sails) on the steam ship and, against a head wind which blows the smoke into them, head south for bleak Kerguelen Island, the only landfall within thousands of miles.

[7] ‘The Rio run’ – from New Zealand across the South Pacific and around Cape Horn to Rio.

[8] ‘Kelpies’ – Evil water-sprites of Scottish folklore; ‘Girn’ – snarl.

[9] ‘Tender’ – The boat which takes passengers to shore.

[10] ‘Rossignol’ is French for nightingale

[11] ‘Close’ – tight or miserly.

[12] Welsh steam coal was McAndrew’s preference. He would condescend to use coal from the ‘Wangarti’ mine in New South Wales, but not ‘patent fuel’ (bricks made from coal-powder), which clinkers up the grills upon which the coals are stacked to burn.

[13] ‘Apollyon’ – the angel of destruction (in the Book of Revelations); ‘bairn’ – child.

[14] i.e. did you feel envy, God, to see Man’s creation? No: man’s joy in creating an artefact is but a glimmer of the joy God had when creating the world.

[15] This reflection reveals the Freemasonry undercurrent of McAndrew Scottish Calvinism. Kipling was an active Freemason (he became secretary of the Masonic Lodge of Lahore when he was nineteen, before the official age for admission). Several of his poems (e.g. ‘The Mother Lodge’) and short stories (e.g. his celebrated story ‘The Man who would be King’) show his Masonic bent. Two basic Freemasonry ideas are: (1) the image of God as an architect who built the world as a temple, according to well-defined rules, and (2) men’s duty to emulate God by improving the world – “we’ll build the Perfect Ship“.

[16] McAndrew’s conclusion from his reflections (“… Always Thy Grace preventing me …”) is that he does not side with Pelagius, the fifth-century British monk who denied Original Sin. McAndrew’s Calvinist conviction is that all his lifetime of service does not guarantee him a place in paradise – only God’s Grace can do that.

[17] The ending brings to a head the dichotomy between the public face which McAndrew “takes on” – here to lecture Ferguson about the cost of coal – and the private McAndrew who decides to heap on the coals and “burn ’em down to port” (thereby losing the commission on any coal he would save), so that Ferguson can reunite sooner with his wife.