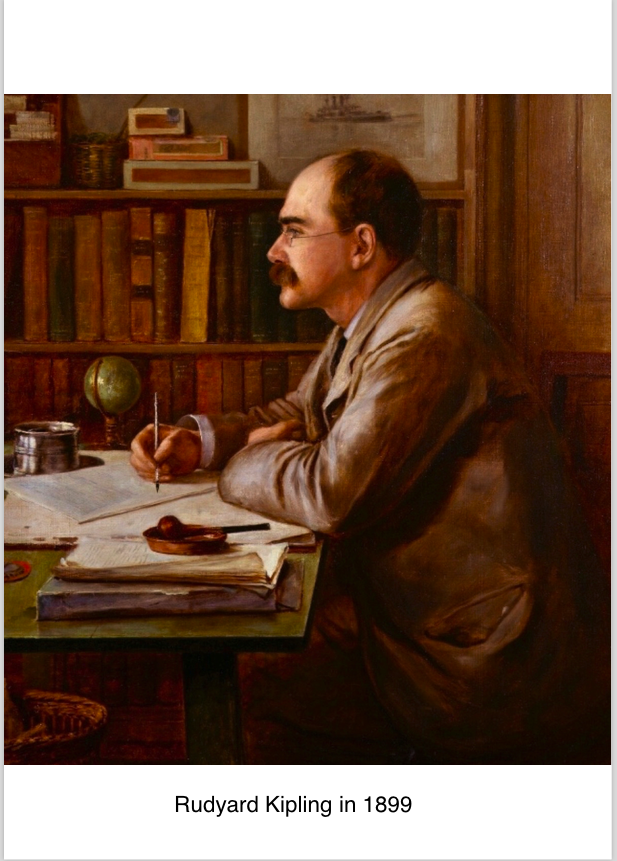

Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936) was an English journalist, short-story writer, poet, and novelist. This site contains Itil Asmon’s selection of Kipling’s poems relevant to our time.

Another selection of Kipling’s poems? Who needs it when the excellent selections by T.S. Eliot and James Cochrane are still available?

I was brought up on Eliot’s “A Choice of Kipling’s Verse”. That volume contains some really great poems, such as “The Ballad of East and West” which inspired me as a teen-ager, and “If–” which gave me and many others encouragement in difficult moments of life. However, most of the poems in Eliot’s selection I found tiresome; so I assumed that since T.S. Eliot was such a great poet and critic, those Kipling’s poems not included in his selection must be even worse and definitely not worth reading. Then I discovered in James Cochrane’s selection some Kipling poems that moved me deeply – such as “The Explorer” and “The Ballad of Boh Da Thone” – that were not selected by Eliot. This prompted me to read “The Definitive Edition of Rudyard Kipling’s Verse”, cover to cover; and to my surprise, I found there many excellent poems not been included in any anthologies. I also found many poems that were written for specific occasions and are no longer relevant, and many others that I found plain boring. Kipling was a prolific writer, who had been conditioned by his early experience as a journalist: much of his verse was written about events of the day, and deserves to be forgotten with them. However, there are real nuggets in the ore – sometimes in the least suspected places.

So far there have been generally two kinds of collections of Kipling’s poetry: the first, critics’ books and articles about Kipling’s poetry which include comments about the poems but without the texts; the second are straight anthologies (e.g. Eliot’s and Cochrane’s which contain a selection of the poems) but without any comments or explanations. Never to my knowledge has there been an annotated selection combining the text with commentaries and explanations.

Rudyard Kipling’s poetry

Kipling was probably the most popular, most widely quoted and best-selling writer of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He has greatly enriched the English language: we use many of his phrases, such as “East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet” (most often misquoted to mean the exact opposite of what Kipling intended), “it will all come out in the wash”, “rock and roll”, “hot and bothered”, “the law of the jungle” or “he travels the fastest who travels alone”, without knowing their origin. His poems and stories were enormously popular with many different audiences – political and military leaders, soldiers and sailors, middle classes and workers, engineers and settlers, adults and children.

Kipling was the first English-language writer to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. However, in the “liberal-progressive” age and especially with the unraveling of the British Empire after World War II, the ideological mood shifted against Kipling. He was accused of being “reactionary”, “jingoist”, “imperialist” and “colonialist”, leading to a wholesale condemnation of his writings (most often by persons who had never read them).Some Kipling apologists take the view that he was a great writer, and for great artists Time pardons “politically incorrect” attitudes. Thus W.H. Auden, who had no sympathy for Kipling’s politics, wrote:

Time that is intolerant To the brave and innocent, And indifferent in a week To a beautiful physique, Worships language and forgives Everyone by whom it lives; Pardons cowardice, conceit, Lays its honours at their feet. Time that with this strange excuse Pardoned Kipling and his views...

It is true that for great artists Time pardons a lot – as it has pardoned for example Richard Wagner’s anti-Semitism and Ezra Pound’s fascism. I have, however, a different point of view: first, that most of Kipling’s poems have nothing to do with imperialistic attitudes, for or against; and second, that those Kipling poems which were labeled “imperialistic” deserve a new look.

Take a new look

Take a new look at those Kipling’s poems containing social and political commentaries that were once called “reactionary”. While many have become dated, I do not know a better satire of the Welfare State than the poem “An Imperial Rescript”, or a prediction of the worldwide financial crisis of 2008 than “The Gods of the Copybook Headings”; nor a better statement of determination to resist appeasement than “Dane-Geld”; or a more clear-eyed view of disarmament than “The Peace of Dives”. When reading those little-known poems to friends, their reaction was uniformly one of surprise: “did Kipling write that?“

Thus I feel that those Kipling poems labeled imperialistic deserve a new look. Not all problems of poorer countries are the result of past colonialist-imperialist domination. Some of their leaders have created for their people worse lives than they had under colonial rule. Kipling’s “imperialist” poems should be re-assessed: maybe his views contain more than a grain of truth.

American audiences deserve to have Kipling’s poetry in a more accessible form. Eliot’s, Cochrane’s and Forman’s anthologies were all published in Britain, largely for a British readership which is generally familiar with Kipling – if only from those poems that are part of every British school curriculum. This selection, in contrast, is aimed mostly at American audiences, whose only exposure to Kipling in all too many cases is limited to Walt Disney’s adaptations of “The Jungle Books” (which bear little resemblance to the original).

Kipling is relatively little known in the United States; yet he had a long and deep relationship with the country. Kipling’s wife Carrie was American; they lived in Vermont from 1892 to 1896, probably the happiest years of his life; some of his best work, including “The Jungle Books” and much of his poetry, was written in the US, and some of it is on American subjects. Had it not been for a combination of personal reasons (a violent quarrel with his brother-in-law) and political ones (a near-war between the US and Britain in 1895 over the boundary between Venezuela and British Guyana), Kipling would likely have settled in the US permanently.

Thus to some extent he may be considered an American writer. More important, American audiences may have an advantage in re-discovering Kipling. Since the US did not have to go through the soul-searching which Britain had undergone after giving up its empire, American audiences may be starting with fewer biases against Kipling for his supposedly “imperialistic” attitudes, and more ready to listen to things Kipling had to say that are relevant to the here and now.

Verse or poems?

Kipling had an amazing curiosity and power of observation with his mind and all his senses, as well as a consummate gift of word, phrase, and rhythm. Probably no writer has ever cared more for the craft of words. The variety of rhythms and stanza forms that he devised is remarkable: each is distinct, and perfectly fitted to the content and the mood that the poem conveys. There is probably no poet who can less be accused of repeating himself.

A word about a question that is of much concern to critics – did Kipling write poetry or verse? Was he a real poet or a mere verse-monger? Kipling himself, with very British understatement, always called his non-prose writings “verses”. To my mind, Kipling at his worst wrote verses – sometimes refreshing, often tedious; at his best he wrote pure poetry, such as ‘McAndrew’s Hymn’ and ‘The Mary Gloster’ that compare well with any of Robert Browning’s dramatic monologues. This anthology contains mostly what I would consider poems, though I have included some writings that must be considered light verse, e.g. ‘A General Summary’ or ‘In the Neolithic Age” – especially if they have a point to make.

I have grouped my selection of poems into fifteen categories, each with a brief introduction. For some of the poems at the bottom of the text are explanatory notes for words and expressions that may not be familiar to some readers.

Finally, Kipling’s poems were meant to be read aloud. His rich and variable rhyme patterns need the ear as much as the eye to be fully enjoyed. At first it might feel strange to be reading aloud to yourself, but try it – likely you will find that it enhances the pleasure of reading these poems.

….. About Itil Asmon